The prison that broke my brain

I was in my mid-twenties, teaching English and wandering through South America with more curiosity than sense, when I walked into a Bolivian prison. Not for work - just because you could. Pay a few bolivianos, walk through the gates, and suddenly you're in this... parallel universe.

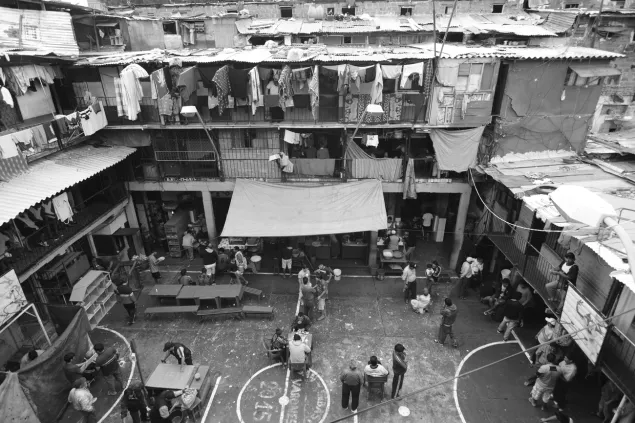

Families lived inside. Not visiting - living. Kids playing in courtyards. Inmates running restaurants, shops, even a hotel where tourists could stay overnight. I bought cocaine from a guy in the prison courtyard (I was young and stupid), ate lunch in a prisoner-run cafeteria, watched children kick a football against prison walls while their fathers watched.

It was chaotic. Problematic. Definitely not something to romanticise. The wealthy prisoners had decent cells; the poor ones slept in squalor. Violence happened. Corruption was baked in.

But here's what cracked open in my brain: justice didn't have to equal isolation. Punishment didn't require removing someone from all human contact and possibility. The system we built in Australia - concrete boxes, extraction, the elimination of variables that might become weapons or hope - wasn't inevitable. It was chosen.

I didn't know what to do with that realisation. But it lodged in me like a splinter.

Learning what extraction actually does

Before I left Australia to travel the world, I fell into 24-hour youth work in Armidale and Newcastle (2004-2006). Residential care, crisis accommodation, the full catastrophe. I was barely older than some of the kids, and I was supposed to be the stable one.

What I learned: every young person who cycled through was there because multiple systems had already failed them. School had suspended them. Family had fractured. Housing had disappeared. And our response? Wait until crisis, then intervene with more extraction.

Take them out of their environment. Put them somewhere "safe." Wonder why they keep returning to the only thing that feels real.

I started noticing: every intervention increased distance between the young person and their community. We called it protection. But it looked a lot like practice for prison.

Queensland: Where reintegration revealed itself as theatre

By 2010, I was working with Queensland Corrective Services, running programs in remote communities and watching young people try to return from detention. Everyone used the word "reintegration" - it was in every policy document, every funding application.

But you can't reintegrate someone into something they were never integrated with in the first place.

We'd extracted them from communities already fractured by colonisation, poverty, and systemic disadvantage. Put them in detention where they learned the specific frequency of institutional despair. Then dumped them back with a case plan and called it support.

I spent three years facilitating programs, developing the Positive Futures initiative, creating films for people transitioning out. Over 300 people completed the programs. Some made it. Many didn't. Not because they lacked motivation, but because we'd designed a system where failure was the most probable outcome.

In the Gulf communities - Doomadgee, Mornington Island, Normanton - I saw reintegration trying to happen. Young people wanting to change. Communities ready to support them. But the system architecture worked against every good intention.

The Bolivia question kept returning: Is any of this extraction necessary?

Spain: Proof that transformation isn't theoretical

Fast forward to 2024. Nicholas and I traveled to Spain to visit Diagrama Foundation facilities. We'd read about them, studied the outcomes, but nothing prepared me for walking through those doors.

Maria's room had sunset-coloured walls. A pillow on her bed said "A Mi Hija" - tomy daughter. Family photos covered one wall. A cordless phone sat on her desk - she could call her grandmother anytime. Her case worker talked to her about architecture school, about what she wanted to build when she got out in three months.

This was classified as Level 4 maximum security. Maria had committed what Queensland would call serious violent offence. In Australia, she'd be in solitary, medicated, counting down years.

Here, she was learning AutoCAD.

When I showed her photos of Brisbane Youth Detention Centre - the concrete platforms, the mesh, the steel fixtures - she went quiet for thirty seconds. Then asked if I was showing her an adult prison.

"No," I told her. "That's for kids your age."

She almost started crying. Not for herself - for them. For Australian kids she'd never meet, living in conditions she couldn't comprehend even after doing what she'd done.

"But how do they learn?" she asked. "How do they become different people?"

I stood there trying to explain that we spend $859,589 annually per child to ensure they don't become different people. That recidivism is a feature, not a bug. That trauma is the curriculum.

She listened like I was telling a ghost story. Then said: "That's not justice. That's just revenge that costs a lot of money."

Out of the mouths of Spanish teenagers in maximum security facilities.

I walked through five Diagrama centres over two weeks. Every one felt like Wonderland - not perfect, but possible. Staff talked about futures like they existed. Young people learned trades, completed education, maintained family connections. Hope wasn't an aspiration; it was operational.

Then I'd fly back to Australia, visit detention centres in Brisbane and Canberra, and feel the hope drain out of the air the moment I walked through the gates.

The gap wasn't resources. It was imagination about what humans can become.

Tennant Creek: The moment I decided to be braver

Nicholas and I drove to Tennant Creek in May, 2025 to build beds with community. We'd been doing this work for months - traveling to remote communities, building furniture with Elders and young people, listening more than talking.

On the drive back, exhausted and covered in sawdust, something broke open.

I told Nicholas: "I need to be braver. I'm writing articles, sharing statistics, having meetings. But the gap between what I'm saying and what I'm seeing feels cowardly."

The Bolivia prison showed me justice could be radically different. Twenty years of youth work showed me extraction doesn't work. Spain proved transformation is operational, not theoretical. And here I was, still being reasonable. Still using policy language. Still playing the game.

"I need to use art," I said. "I need to own something so I can dedicate myself to a vision."

The idea arrived fully formed: buy a shipping container. Give people 10 minutes to feel what Brisbane detention actually feels like. Then 10 minutes in Diagrama. Then 10 minutes with grassroots programs showing what's already working.

Not a report. Not a presentation. Thirty minutes where policy meets flesh and blood.

I wanted people to sit in it together, then make sense of it together. Because that's when conversations hit different - when you've felt the same fluorescent hum, touched the same revenge furniture, then walked into proof that none of it is necessary.

Building it with my daughters watching

We bought a shipping container and hauled it to the farm in Witta. Nicholas and I started building. Wiring the electronics. Painting walls that specific shade of institutional grey. Installing mesh so fine it pixelates hope.

My daughters were there, they held the nail guns, they painted walls, they supported what this needed to be. I wanted them to see: when something matters enough, you don't wait for permission. You buy the containers. You learn to wire lights. You get your hands dirty.

I chose the exact frequency of fluorescent lights (120 Hz - the one that seeps into your molars). The precise colour of concrete. The specific grade of steel mesh. Not to be dramatic, but to be accurate. Because if people don't feel it in their nervous system, they won't understand why we need to blow the whole thing up and start over.

Young people as architects, not subjects

Then we brought in young people through Interlace Advisory - Kate Bjur and G Rangiawha connecting us with Isaiah and others who'd survived the system. They were joined by the incredible Christine Thomas who brought incredible grounding and trauma informed conversation to the mix.

They didn't consult. They designed.

When Isaiah walked into Room 1, his shoulders shifted. That specific muscular contraction of someone whose spine remembers surveillance cameras like a second skeleton. He picked up something sharp and started scratching the walls - not vandalism, but archaeology in reverse. Leaving evidence of the future in marks that mirror the past.

Two of them had been in rooms identical to Room 1. They knew the fluorescent frequency because it lived in their skeletal memory. Their philosophy became the project's: "You can't unknow what you know, but you can choose what you build next."

What CONTAINED actually is

It's a 47-minute answer to the Bolivia question.

I can't make politicians visit a Bolivian prison or spend three months in Spain. But I can compress the essential experience:

- Room 1: Feel what we're currently doing (Brisbane detention reality)

- Room 2: Feel what's actually possible (Diagrama's proof)

- Room 3: Here's how we build it (CON|X infrastructure + grassroots programs)

I'm not trying to reform the youth detention system. I'm trying to make it obsolete.

Like mobile phones made landlines irrelevant - not by criticising them, but by being undeniably better.

What I want people to carry

48 hours after walking through CONTAINED, I want them carrying a question they can't shake:

"If Spain can do this with young people who committed serious violence... if Indigenous healing circles in Alaska hit 97% success... if community programs work at 1/10th the cost with better outcomes... what the f%$# are we actually doing?"

Not guilt. Not shame. Just: What are we actually doing, and do we have the courage to choose differently?

A Curious Tractor's role

This is what Nicholas and I built A Curious Tractor to do. We don't write more reports. We create experiences that shift perception at the nervous system level, then provide practical infrastructure for communities to act on that shift.

We built CONTAINED because someone had to. Now it belongs to anyone ready to feel it, then do something about what they felt.

From Bolivia to Brisbane, it took twenty years for this to become clear. But once you see it, you can't unsee it. Once you feel it, you can't unfeel it.

The door opens when you're ready.

.svg)